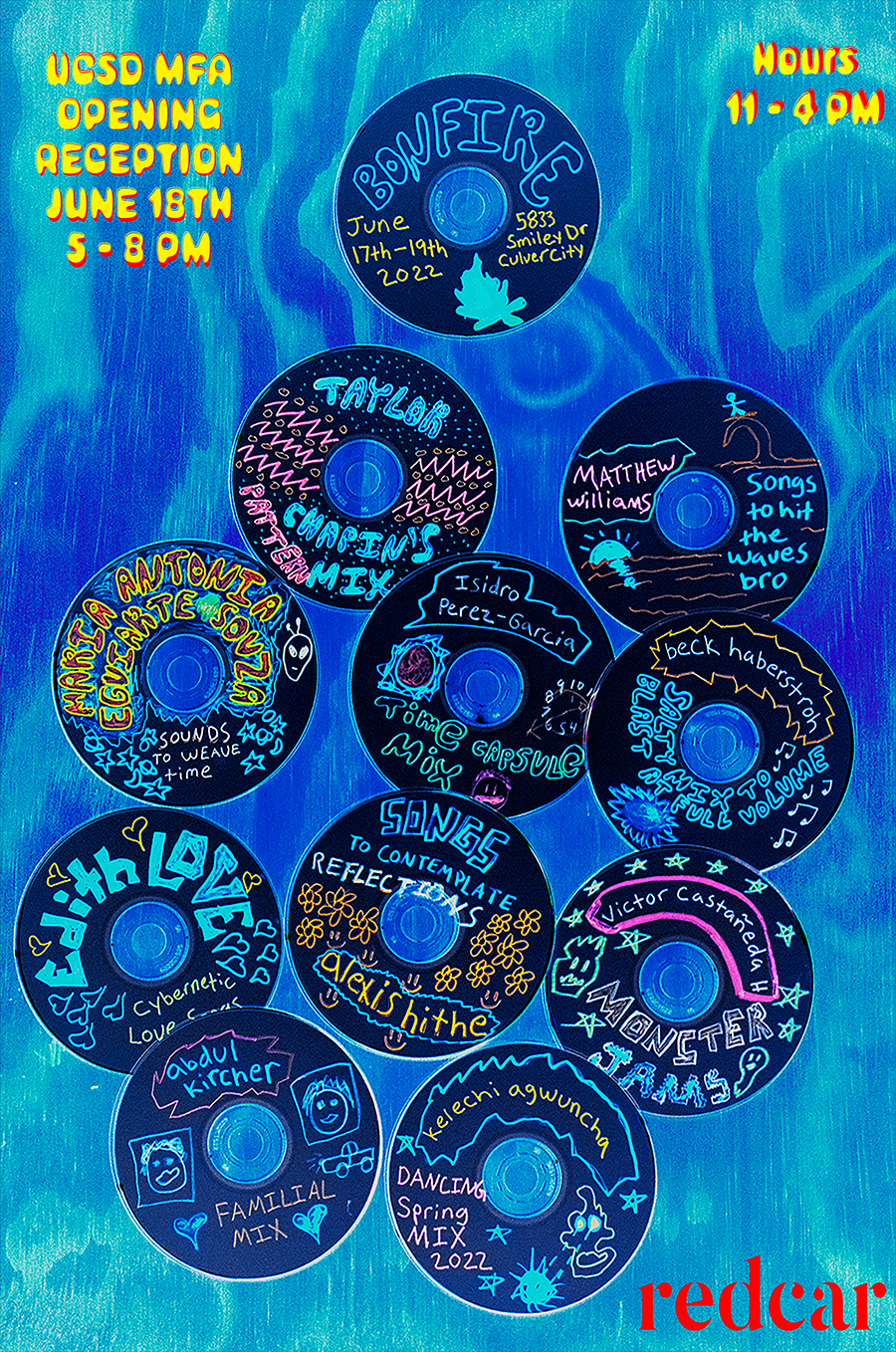

Bonfire

2022 Graduating MFA Exhibition

Reception: June 18, 5:00 - 8:00 p.m.

June 17 - June 19, 11:00 - 4:00 p.m.

5838 Perry Dr. Culver City CA

Visit the Grad Exhibitions site to learn about the MFA Thesis Projects.

Taylor Chapin, Maria Antonia Eguiarte Souza, Matthew Williams, Isidro Pérez García, beck haberstroh, Edith Love, alexis hithe, Victor Castañeda H, Abdul Kircher, and kelechi agwuncha. With support from Redcar Properties Ltd.

A bonfire is, by definition, a large open-air fire used as part of a celebration, for burning trash, or as a signal. The etymology of this word is derived from the Middle English bonefire meaning, literally, a fire made of bones. In coastal regions, such as California, it is common to have a bonfire on a beach, particularly at the center of parties. A bonfire is a communal activity – another version of bonfire is boonfire, which suggests that the practice of burning a large fire be done with close companions. Bonfire, then, seems a fitting name for this group showing of the UC San Diego 2022 MFA cohort. It is, first and foremost, a celebration of their time developing as artists, and also as a community. We might also think of this as a cleanse of sorts, as fire has historically been lauded for its purification powers. Perhaps this bonfire might function as a controlled burn: cleansing the group in preparation for this next phase in their lives. And lastly, we could also receive this show as a signal – an acknowledgment of how these artists have created their own languages with which to engage the world.

In mounds, alexis hithe presents a film installation composed of mirror shards and two solo dance videos projected onto the structure, which is then reflected onto the nearby walls in the space. A reconstitution of another film installation, this work explores histories of the Black experience and that of the Cherokee nation. hithe challenges conventions of representation through the literal and conceptual shattering of forms. In bringing these two parallel histories together, she engages in a critical empathy: looking simultaneously inward and outward, like the installation itself. In the words of the artist herself, "mounds wonders whether a body is an experience of its own, and whether this experience can drive settler colonial campaigns of chattel slavery and indigenous genocide further towards obsoletion."

The performing body is also central in the video works of kelechi agwuncha, who presents two versions of tether, which combine playful, cyclical performance elements inspired by their childhood memories of Igbo Ojionu masquerades and tetherball. In the first version we see a single video projection, a red monochrome, in which the artist repeatedly jumps up and down, swinging a tetherball overhead as the camera moves around them, while dressed in a metallic fringed outfit reminiscent of the traditional garb of Igbo Ojionu masquerade. We hear the artist describe playing tetherball as a spiritual gesture of "continual flight" and "a thrust above." Other voices talk through their experiences of Blackness and speculate upon gestures of flight. The second presents a tether pole, covered in the same metallic red fringe from the video, with a four channel monitor attached to the side in which we see various analog versions of this video.

Rotation functions similarly in a new video work by Edith Love which combines digital sculpture and poetry. The artist uses her own body's likeness merged with natural forms: a reimagining of reality. In her own words, "I like that in the imaging techniques I use now, I make my own light and it is cast out at the viewer, rather than trying to capture external light and then reflect it." Love uses image capture technology and then relights the rendered form in virtual space. The bird's nest and hands call to mind ideas of cradling. The video cradles the form through the persistent rotation, letting us see the form in its entirety, and asking us to read the poetry, affixed like leaves to the form, with intention.

Victor Castañeda H's sculptural work, Science & Legs, also merges reality and imagination, through exploring the fallacy of memory. He uses paper mache and found objects as a way of filling in the gaps of his own memory – inviting error in places of doubt or disremembrance. Inconsistencies become integral. These works are often presented alongside sound and VR pieces, which further develop these partially fabricated memories.The artist's DIY approach and color choices are distinctive, reminiscent of both punk and underground queer aesthetics. According to Castañeda H, "the creatures and figures I create come from that hot summer suburban fantasy placed within my own memories. The Valley and my own personal archives have become a new imagined narrative." His sculptures are at once delicate, playful, and assertive.

Similarly vibrant and playful in their colors and patterns, Taylor Chapin's paintings employ illusory facades to distort reality. She refuses us both object recognition and the identifiers of human individuals, things that structure our relationships to capitalist consumerism and also identity politics. Brand identities, such as the Haribo Goldbears in her painting and installation Still Life with Haribo Goldbears, are obfuscated, like the various facets of the intersectional identity of the figure in her painting Thank You For Joining Us Today - things like race, gender, etc. are unreadable, or at least uncertain. From Chapin's own artist statement, "the wrapping of the body in this large-scale, painting format seeks to critique the predation of the advertised body by highlighting it as a manufactured empty vessel used to divert the attention of the American consumer."

Matt Williams's sculptural works are created through subtle acts of destruction and enact formal metaphors related to control. On Again Off Again uses polyester resin, phosphorescent pigment, and wire to create a suspended sculpture reminiscent of a light fixture. There is a humor in the conflict between the form and its function: the lights in a given space must be turned off in order for the phosphorescent pigment to glow. Unlike a light fixture, the luminescence of the sculpture comes from the surface, not the interior – an inversion. Stunted again employs irony as the sculpture, made from wood and aluminum, looks as if a silver cap has been imposed to prevent a wooden structure from growing. Williams says, "this work was informed by my thinking about destruction as it relates to creativity and how an armature may be externalized."

Rotting from Within is an eight year documentary photography project by artist Abdulhamid Kircher. What began through a simple documentary impulse evolved to engage with various aspects of the artist's life, primarily through the lens of his relationship with his father and his grandparents who live in Turkey. Kircher looks at the disparity in the beliefs and practices of various guardian figures and processes this through photography and writing in a once private journal, included as part of RfW #1, a collage of various prints, scans of his writings, and familial objects. The images range from portraits, to fragments of bodies, patterns, the landscape, and architecture. The collage resembles, as accurately as one might imagine, memory itself. Fragments, repetitions, small daily things that might seem mundane, but are otherwise beautiful.

Photography again plays a crucial role in the work of artist beck haberstroh, "I re-perform analogue photo processes as a way to tangle contemporary issues of legibility, representation, and power." In their series of large scale salt prints presented on bed frames, Our Body is the Limit of Our Image indexes their own biochemical signature onto cloth through sweat. This is then treated with a silver nitrate solution and exposed in sunlight to create abstract traces of the body. Another series of images uses cast faces from people in their community that have been vacuum formed to create plastic molds, and then printed as photograms which create distorted portraits. Community and care are central to the way haberstroh engages with image-making.

Maria Antonia Eguiarte Souza also centers her art practice on care, felting objects to create sculptural installations that both occupy space and also invite viewers to take up space. Steeped in spirituality and practices of feminist and queer subversion, she practices self-care through artmaking as a survival strategy. She communes with Saint Teresa of Avila and holds space for her through performance and effigy. Her video exercises extend regular moments, basic human rituals, to the point of absurdity or reverence. To Eguiarte Souza, anything can be sacred, but nothing is more sacred than time, which she asks for and gives of freely. Drawing upon early conventions of performance art, she finds the sublime in the mundane.

Artist Isidro Pérez García questions ideas of modernity and tradition while investigating themes of indigeneity, capitalism, and migration. Working across a variety of media, Pérez's artworks contribute to anti-colonial histories. Outside on the patio, he will facilitate a popup pulquería, where pulque, made from the maguey plant, will be served. Pérez says that, "the pulquería pays tribute to how archives should and do exist in the collective memories of communities and their biocultural relationships, despite the distorting force of borders. It is a way of re-engaging with the living biocultural archive that exists within our kinship with the maguey." In Huasteca Hidalguense, where the artist is from, an entire cosmology and way of life has developed around maguey, which the pulque is representative of. For immigrants like Pérez, crossing the border also serves as a change in cosmos.

With such different subject positions as well as material and conceptual interests, these works may seem rather disparate upon first glance. However, they share several of the same concerns, and were also made in community together. Community is truly a central tenet of each of these artists' practices, merely in different ways. We can see the ways that hithe, agwuncha, haberstroh, and Kircher engage in different processes of image-making to challenge representation and ways of knowing themselves and others. We can see for Love, Castañeda H, and Chapin how the slippage between surface, material, and form allow them to question dominant narratives, memories, and even the body itself. We can see how Williams, Eguiarte Souza, and Pérez's interdisciplinary practices explore new ways of engaging with materials and the various histories that run parallel to them and also intersect through them. There are many connections that thread and, at times, stitch the works of these artists together. A bonfire is a celebratory burn. People drink and revel in community (talk, kiss, etc.) while illuminated and warmed by the flames. This Bonfire is revelatory, cleansing, and a sign of great things to come from these artists.

– Dillon Chapman (MFA 2020)